French photographer Frédéric Lagrange first became intrigued by Mongolia as a child, after his grandfather – often a reticent character – told a vivid story about being rescued in Germany towards the end of World War II by Mongol soldiers.

“He was fighting along with the British, Americans and French in Germany and got caught and sent to a German prison,” Lagrange recalls. “It was the winter of 1944 when a battalion of Mongol soldiers were fighting in the area and set the prisoners free. As a child, when he was telling me the story, I saw the excitement and that it was a very important event that happened in his life. He was very quiet and not a very expressive person, so for him to be able to tell a story like that I knew it was very important in his life.

“That was something I really kept in my head, that event. Also those people involved coming from a place I had never heard of, a place I had never been to. Mongolia’s always had a bit of a magic in its name as well – for the people, for the place.”

Part of this magic comes from the sense of mystery attached to Mongolia. Rarely in the news in Europe, it has become symbolic of a far-flung, ends-of-the-earth place.

“It’s something you hear about but you never really know too much about, so there’s a sense of mythology, a sense of intrigue about the country,” continues Lagrange. “You hear about a lot of countries around the world but never really much about Mongolia. Or, for that matter, any other central Asian country.”

Top: Descending into the city of Bayan-Ölgii, Bayan-Ölgii Aimag, Western Mongolia, 2015; Above: Portrait of a herder’s daughter against black fabric near Üüreg Lake, Uvs Aimag, 2001

A marmot hunter returns with his catch hanging from his motorbike. Üüreg Lake, Uvs Aimag, 2001

Lagrange first travelled to the country in 2001, for a month-long trip in the late summer. At the time he was working as a photographer’s assistant in New York, and he describes that trip as being motivated by a desire to travel more than to photograph, though he did take a black backdrop with him in order to shoot a set of portraits.

His interest turned into a ‘project’ when he returned the following year, this time in the winter. “I knew the conditions were definitely harsher and the winter is very, very extreme,” he says.

This impacted on the photographs he was able to produce, particularly as he was shooting on analogue film. “At -30 degrees, that camera just freezes, it doesn’t work at all,” he says. “And the film also, there is always the risk that when it’s exposed to the cold, the extreme cold, it doesn’t really process the same way. So all those things were very challenging, but that really was the medium that I wanted to follow through with because I thought the quality was much better.

“It made everything very unexpected,” he says of the weather. “I would get into situations, and they would very often turn out to be incredible moments, where I ended up shooting some very powerful moments… To me there was an additional complexity to shooting in the winter but the results were definitely worth it.”

A caravan of camels carry a family’s possessions. The family was travelling to a different pasture where their cattle could feed on fresh grass. Uvs Aimag, Western Mongolia, 2004

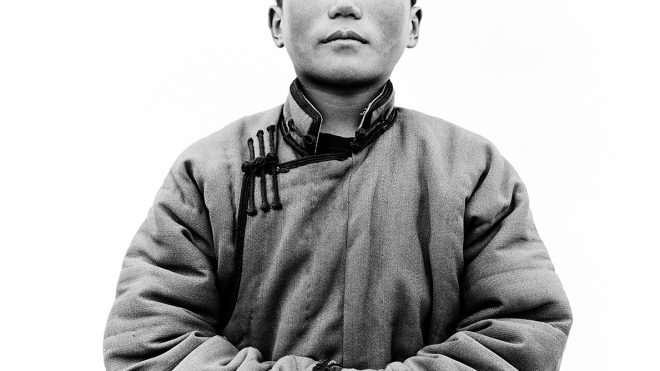

Portrait of a young herder boy against a white paper backdrop. South of Khövsgöl Lake, Hatgal village, Khövsgöl Aimag, 2006

Lagrange’s work in Mongolia turned into a long-term passion project, with him returning most years to the country, usually for month-long stretches at a time. When he decided to bring the project together in a book, he therefore had thousands of photographs to choose from.

He initially reached out to traditional art book publishers to produce the book, but felt frustrated at the lack of involvement he would have in its creation if he went down that route. “The way they work is basically me sending them maybe 300 images, and they come back to me maybe six months later with their own text, their own layout, their own edit, their own everything,” he says.

This led him to creating a Kickstarter to fund the publication, which features design by New York Times Magazine art director Matt Willey and a foreword by writer Pico Iyer. “After spending so many years, and so much time, and so much money on this, I felt we needed to do something that is very much the vision of a group of people I respect very much in the industry,” says Lagrange, “that I love to work with, and for us to decide what to do with this.”

Some modern Mongols are herding cattle with Chinese-made motorbikes instead of horses. Üüreg Lake, Uvs Aimag, 2015

A spread of snacks, sweets, and Mongol tea are laid out to welcome guests. Whenever Lagrange and his team stopped, they would be welcomed into people’s homes. Often, having guests was the only way to get news from other parts of the country. Tsengel village, Bayan-Ölgii Aimag, 2004

He’d previously worked with Willey on projects for Port and Avant. “I really like his minimalism, his work is very elegant,” he says. “It’s very masculine, very strong, but there’s sometimes an incredible lightness and elegance to it.

“Most of the time when I see layouts he has done with my work I see the images [from] a completely different angle. I really wanted to be able to have that kind of surprise and let Matt do his magic with this.”

The resulting book (which has surpassed its Kickstarter target, but still available for pre-order until October 26) is large-format and features 185 images. With a limited edition run of 1,000 books and a price point of $285, it is perhaps closer to an artwork than a regular photography book. Lagrange acknowledges that “the book is not for everyone”, but that for his first book, he has been able to create exactly what he wanted.

As to his love affair with Mongolia, he can’t see this ending any time soon. “I need to have my dose of that place, a dose of that immense beautiful landscape, of the people,” he says. “I love to go back every year. Now also what I try to do is actually to take people with me, to travel and do some photography workshops in Mongolia. I take a few people with me and take them to some of the places I’ve visited and explain how I proceeded on that project. So I’m going back definitely.”

Portrait of an officer and his wife shot against black fabric. This image is from a series Lagrange shot while stranded on a military base during a snowstorm. Tsengel village, Bayan-Ölgii Aimag, 2004

Young herder boys pose in front of a white paper backdrop. South of Khövsgöl Lake, Hatgal village, Khövsgöl Aimag, 2006

Mongolia cover and slipcase

Mongolia by Frédéric Lagrange is available for pre-order via Kickstarter, more info is hereThe post Frédéric Lagrange: Inside Mongolia appeared first on Creative Review.

Frédéric Lagrange: Inside Mongolia

By Thomasin Creative News670